Migrant Bodies is a project created in partnership with Comune di Bassano del Grappa (Italy), La Briqueterie – Centre de Développement Chorégraphique du Val de Marne (France), Circuit-Est Centre Chorégraphique (Québec), The Dance Centre (British Columbia) and HIPP The Croatian Institute for Dance and Movement (Croatia). Migrant Bodies invites 16 artists (Alessandro Sciarroni, Su-Feh Lee, Manuel Roque, Cécile Proust, Jasna Vinovrski as choreographers/dancers; five writers, five visual artists) from three European countries and two Canadian provinces to carry out two years of research on migrations and the social and cultural impacts that migrations generate in local societies, in order to produce works to be staged in established and renowned venues, or in site specific locations, and to portray new forms of identity of the migrant bodies to the wider possible audience. The project is supported by the EU Culture 2007-13 Programme. Here is the report by the blogger, writer and free-lance journalist Anna Trevisan who has been involved in the project.

Migrant Bodies:

possible interpretations

Imagination and migrant bodies

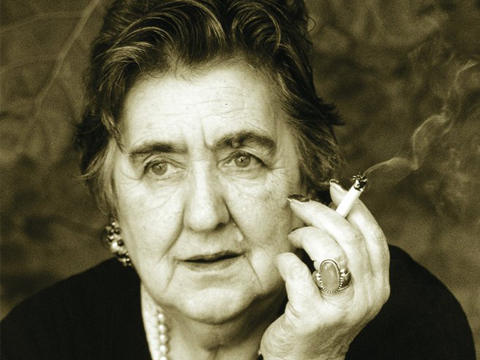

Alda Merini

The poetess Alda Merini wrote: “The only root I have hurts me”.

I think that being a migrant body means a radical change of scene, muted and continuous, a strong reminder of roots of the land which bore us and yet nevertheless urges us to part from it, go beyond it, further away.

I reckon that roots are exactly that: a tiny hidden pinprick that stings the eyes and heart, and that pulses rhythmically in the brain signaling to block its origin, to turn off the pain, setting in motion, moving on. This tiny pinprick forces us to walk, to move, to turn a focus of pain into motion, into dance, into invention, into generation, into imagination or literal migration from an old to a new life, from the land of origin to land anew.

All of us are foreign migrants in a sense. We are all able and know how to inhabit many worlds, in both the real and the possible universe. Just imagined and imaginary worlds; lost worlds or those we live in here and now. However, we are not all migrant bodies in the same way, to the same intensity, and for the same reasons.

We migrate when we transform ourselves, when we move and travel, even if only via our imagination and emotions, experiencing both sides of migration: the lightness of flight and the gravity of becoming flesh, to reassume and reside there, the wonder of its apprehension and the desire to leave.

We migrate when performing physical movements, large and small, generating a cascade of many other changes; minor and major perceptual landslides that are emotional, gestural, cultural, linguistic.

We migrate, sometimes without choice. It is the transformation obligated by escape: escape from death, escape from disease, escape from suffering. When we did not choose the transformation of the body, nor choose this crossing of borders, so radical and unequivocal – emotional, intellectual, geographical, cultural, linguistic… – then, to be migrant bodies become daunting, impending, overwhelming.

Alessandro Sciarroni performing his “Turning”

Ludovico Ariosto – who wrote of Astolfo’s voyage to the Moon, in Orlando Furioso, his epic poem of 1532 – and Giacomo Leopardi – who penned illustrious poetry dedicate to the Moon – were migrant bodies, traveling, transubstantiating into new dimensions. Migrant bodies since they were anticipatory, precursors, portents.

My ancestors were migrants: miners in Switzerland, with the burden of a large family to maintain in Italy.

Our body, as Alessandro Sciarroni likes to think of it and how the biologist Pierre Bissonette construes it, is itself a migrant; its conglomeration of cells is in continuous motion, within us, perpetually migrating.

I am and I continue to be a migrant body, when I speak and write in English. It is not my mother tongue, therefore I do not think in English or live through it. You see a word is body, voice is body, language is body.

I am a migrant body when I speak French, just like the immigrants I met, strained to translate themselves into a language —Italian —one they do not know, forced to produce novel sounds, voices that are no longer their own, with breath appropriated by new words, and that motion of the throat, neck, mouth, nasal cavity and diaphragm all working in an unfamiliar way.

Linguistic migration is an invisible form of migration within the body. It reshapes posture, intention, voice, thoughts.

Memory and Migrant Bodies |For Ginelle Chagnon and Cécile Proust

When I was asked to participate in this project as a writer, I immediately thought of interpreting the migrant body theme in a political sense, in a social sense, as a territory of struggle. The meeting with Italian activists like John Mpaliza and Anna Zonta consolidated my initial idea of the migrant body and I decided to amplify their voices, their stories. I wondered how to narrate them, what form would be the most faithful, most loyal, least duplicitous. Writing about someone always involves a certain misrepresentation. So I decided to let them speak themselves, recording audio clips to document our conversation-interview, and so match the transcript to their speech.

Albeit naive, I think it is the expedient way to yield a greater truth for their testimonies, to conserve the integrity of these migrant bodies, through their own voices.

Ginelle Chagnon. Courtesy of Matteo Maffesanti

Then Ginelle Chagnon, the Migrant Bodies mentor, had patiently subverted my initial vision, encouraging me to conceive of migration as memory, or rather memory as a key to migration.

That’s how one of my texts became included in Cécile Proust’s production Ethnoscape whilst in Italy. The text is entitled Milk. It centres on a road, still there today, one I have travelled down many times going into town. It stems from an account passed down from my grandmother. A historical event – the hanging of partisans in Bassano del Grappa on 26 September 1944 – fused in history, and into the present day. Indeed, just as I was writing my piece, my grandmother’s recount, a boat full of migrants sank off Lampedusa. The news, coupled with this memory, created a mental loop and all suddenly appeared quite clear: my memory, my grandmother’s memory, the recollection of an escape, a civil war, of despair; they had been embodied in those migrant bodies, and came back to me thanks to them. They, those bodies of migrants, in a trice I knew them, knew their stories, their desperation, their fight.

These bodies of migrants, only just drowned, were those same lynched bodies, reemerged from faraway ’44, and vice versa.

Migrant Words | Monolingualism, Bilingualism and “Babel-lingualism”

When the Italian government took control of South Tyrol after the First World War, the first thing that it did was to erase the German language overnight. It imposed Italian in schools, forbade the publication of newspapers in German, it foisted Italian editions instead. Then it installed the Italian Post Office and Carabinieri paramilitary, and built houses using cement and concrete in place of wood and stone. Then came the bombing and the deaths. Then came the forced bilingualism, continuing to this day, along with resentment.

Nowadays the Italian language is no longer a country. It’s just a land to be crossed, a boundary to be disavowed.

Nowadays Italian is not spoken much. A dialectical tongue, basically. A minority language, somewhat elitist (for the Vatican or educated foreigners and engagéwho study in cultural institutes abroad).

Nowadays, those who don’t speak English don’t exist. Sense doesn’t emerge. I try to speak this beguiling language that I cannot use, that I do not grasp but deem that I love because it floats in my mouth and on my palate like a ping-pong ball and produces funny, contorted phonation.

Cécile Proust and Marie Claire Fortè. Courtesy of Cris Dusi

The voice, my voice changes when I speak in English. This shows that even the voice is the body, the language of the body and also thoughts “peel off”, fall, get hurt if they are not prepared to migrate barefoot. Speaking in English is like migrating barefoot. This migration can be as soft as walking barefoot on lush grass, when your sentences come out correctly and efficiently. But it becomes as excruciating as walking barefoot on shards of glass when you try to utter concepts in real time yet don’t respect the timing of the cadences, thwarting the translation’s chance to breathe.

When I met the dancer and writer Marie Claire Forté in Bassano, during the Symposium on the 3rd and 4th of July 2015, she spoke of her bilingualism, a priceless treasure, in my opinion, because it had been born out of love: Marie Claire inherited two languages from her parents. But Marie Claire also acquainted me with the bilingualism of Native Americans. Italian, my native language, is today essentially a “reservation”, like an area set asunder for Native Americans, but its boundaries are intangible, something Italians are often unaware of or they want to delineate at all costs.

The perilous relationship between language and power enters into our day-to-day lives. Trapped under our skin, we carry it around almost without realizing. We still speak of “the indigenous”as if they were “peoples of other continents”, in other lands, other countries, and we picture them as black, naked, with spears and tattoos, despite the culturally correct reiterating that conditions have moved on, this brazen colonial imagination endures. Yet, we know not how to expunge this imagery. Perhaps it’s because it has become part of us, we are in turn traversed by others and it leaves us empty. We are indigenous to the Italian language.

As a young girl I was ashamed of the Veneto regional dialect, it was the language of the poor, the powerless. The language of culture, however, was the language to which I wanted to belong. I spoke a refined Italian, apposite, polished; I voiced Italo Calvino Italian. But nowadays I feel a profound tenderness for the dialect of my grandmother, an ardent appreciation for those few sentences that I was able to learn but don’t know how to translate well into Italian, because they are able to articulate something that Italian simply cannot do justice to.

Thanks to my bilingualism (or lack of) I finally fathomed what the myth of the Tower of Babel alluded to.It’s not about God who gets angry because men discover how to become gods. God doesn’t get angry because people try to raise a tower to heaven. God is angry because the tower eliminated other languages, it hid them, it disintegrated them, it forgot them.There is a deceit in this story, the tale is the other way around, a sort of red herring as in the best who-done-its. Multiple languages are not God’s punishment. The punishment is that tower, the punishment is the unilateral and dominant wish to rescind them, to erase them all. God knows, but doesn’t say, and he imparts the opposite to us, an “upside down”legend, to avoid exposing the ruse, to make us learn on our own.

Silence and migrant bodies. For Jasna Vinovrski and Su-Feh Lee

Jasna Vinovrsly performing her “Standing Alive”

I do not know if the storm that day came because we were in a bad mood or if we were all in a bad mood because the storm was coming. But it arrived. Ginelle Chagnon had taken pictures of that electric afternoon, of the fraught atmosphere, in Garage Nardini, to speak about silence and words.

The storm deflated into a gloomy downpour, pelting, purging. First, the magnetism had unified our discussions, it forced them to collide, to burst.

Jasna Vinovrski spoke of political silence, the need to break that silence and Su-Feh Lee stressed the impossibility and inability to break that silence. Cécile Proust recited George Perec’s poem Je me souviens.

“Don’t ask us the word to frame / Our shapeless soul on all sides”- whispered the italian poet Eugenio Montale. Theodor Adorno stated that breaking the silence after the Holocaust by way of poetry would be a barbaric act.

Paul Celan “replied” to Adorno by writing a sublime poem: Todesfuege (DeathFugue). Rereading it now makes me shudder. After the silence of reticence, the silence of empathy, the silence of incumbent listening, the silence of devotion, the silence of emotion, there was the silence of words cascading dumbfounded. After the complicit silence, after the guilty silence, after the conspiratorial taciturnity that had turned off the tears to those massacres, after the political silence, after the silence of the murderer, after the silence of tortured bodies, the raped women, dismembered limbs. After the silence of horror, which also freezes glances and condemns them to stone, comes the word.

In the CIE- Centro di Identificazione ed Espulsione (Identification and Expulsion Centre) Crotone (in the South of Italy) was taciturn in that hot summer of 2009. A loud silence, deafening. A drawn-out, stubborn silence all around. No one wanted to talk. No one wanted to say anything. It was an unbearable silence, infinite. Neither could I find the right words to say in order to break that silence.

Su-Feh Lee

Mine was the silence of shame. Because I was very ashamed to be there, to have discovered that part of the system. To be dominant, without having asked. By birth, not merit. Not demeritorious, however, in the subordination of all those people, men and also many women and children, gathered together in forced cohabitation within a torrid repository. Without intention, without having sought it, forced to share intimacy with strangers due to one thing in common only: the wait for Italian papers or otherwise forced repatriation. People who don’t even speak the same language, who don’t follow the same religion, who don’t even share the same reasons for emigration: some people flee from war, others flee because they are homosexual. Some people are fleeing massacres, others fleeing hunger. These are the most wretched of all because, in Europe, famine is not recognized as enough of a risk, it is not a sufficient requirement for seeking asylum.

That day, sitting around the table, we looked out at some graffiti on the wall of the garage courtyard. It read: “speechless”. That sounded like an anonymous response to the question that had been tormenting us for days: “Can the subalterns speak?”.

Dance and Migrant bodies. A prelude

The Protocol | Improvisation as Migration.

Deconstructing ego: from an individual to a collective identity

What does it mean to improvise in performance?

“[…] It has something to do with the ability to continue to make your own choices when you improvise with others, and when you make physical contact with someone, in what way are you directing them or forcing them to play your game” Nancy Stark Smith remarked during a 1990 seminar held during the Movement Studies Program in The Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

“How do you work with each other’s material? When are you going too far? When are you making decisions for your partner? When are you boxing them in? And when are you too distant? When are you just sort of not relating to each other?” she queried.

The Migrant Bodies team in Bassano del Grappa

These are exactly the sort of questions we debated and the sort of internal dynamics we pursued as a group during our Migrant Bodies seminar in Bassano. A non-aggressive ring in which we assembled together, we embraced each other, and we boxed, we checked our patience levels, measured our self-control and our (in)tolerance to diverse artistic approaches to the topic that we had to debate and nurture, the aim of our workshop. We experimented with the enforced sharing of a common space, prolonged over many days. We explored the intentional absence of decisive leadership and the fatigue of building a team.

Shrewdly our mentor, Ginelle Chagnon, just chose to observe us and let us appraise each other without interference, unless specifically requested. She allowed our emotions circulate, as well as our thoughts, our resistances and moods, our bodies and minds without leading us, only suggesting a direction.

By inviting us to follow her along a not so commonly travelled path, far away from the world wide spread of macho stereotypes of leaders, Ginelle Chagnon gently brought us to the most challenging exercise at all: listening to each other. Accepting to disagree with each other, to collide against our will and to find quick solutions were the cataclysmic rules of the game: a grand rehearsal for the collective migration finale.

Manuel Roque performing at CSC Garage Nardini

Ginelle Chagnon organised our meetings in two parts: practical exercises in the morning, conversation in the afternoon. The goal of our daily conversations was to build from scratch a common improvisational vocabulary. Cécile Proust proposed the Simone Forti protocol; introducing structure into our conversation with simple and basic rules such as “don’t speak while someone else is talking”, “you can speak for a maximum of three minutes per turn”, “you have to wait for your turn before replying” and so on. The quality of our interactions changed profoundly after this regime was implemented. We were all sitting around the table, in a circle. The conversation had become more disciplined and well organised, the dissent less personal, more reasoned and comprehensible. The internal rhythm of each contribution more concise and meaningful, the general pattern of the conversation more harmonious. Each individual was allowed to emerge from the group without fracturing the whole. A new form had been created: its bounds were more fluid. A choral shape with a wide internal circulation of individualities, languages and personalities.

These improvisation schemes, adopted for the Bassano workshop, upheld everyone as an individual, yet at the same time compelled each member to relate with one another. A lone speech could become part of a larger discourse about migration. The group transformed itself into an autonomous creature with its own life force. Improvising in performance entails an abdication of your own final intention and destination; it implies a renunciation in order to let your own perspective prevail and dominate the meaning and result of the whole process, because it urges you to lose control. Improvisation in performance is the first step in letting your artistic identity migrate toward unknown paths, unknown territories. Improvising with a group of artists from different backgrounds induces a migration for all. Migration as unexpected encounter, as new zone of reflection, as new unplanned creation.

Text by Anna Trevisan

English Translation by Jim Sunderland

Tags: Migrant Bodies