English translation follows below

All’intervista via Zoom Muna Mussie arriva sorridente, dentro ad una felpa verde. Sorride quando pronuncio il suo nome e con garbo mi corregge. Ascolta con puntuta dolcezza le mie domande e intesse con infinita pazienza le sue risposte, conducendomi poco a poco dentro al suo mondo, popolato di oggetti, ricordi, connessioni dove passato, presente e futuro si allacciano circolari. In alcuni momenti mi sento disorientata dalla conversazione, che lambisce zone ad alta intensità emotiva e picchi raffinati e colti. Mi sento spostare gli occhi da dita invisibili, che mi indicano altre direzioni, altre risposte. Muna cuce e scuce mille volte il nostro discorso, inserendo pause, digressioni, nuove partenze, salite che forse sono in discesa. Questa intervista è un lavoro di tessitura a quattro mani, dove trama e ordito, intervistato e intervistatore, intrecciano insieme un discorso.

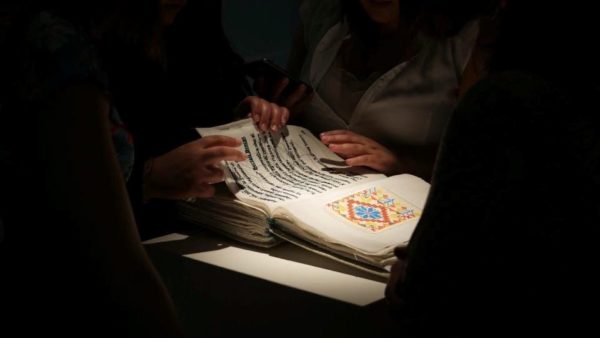

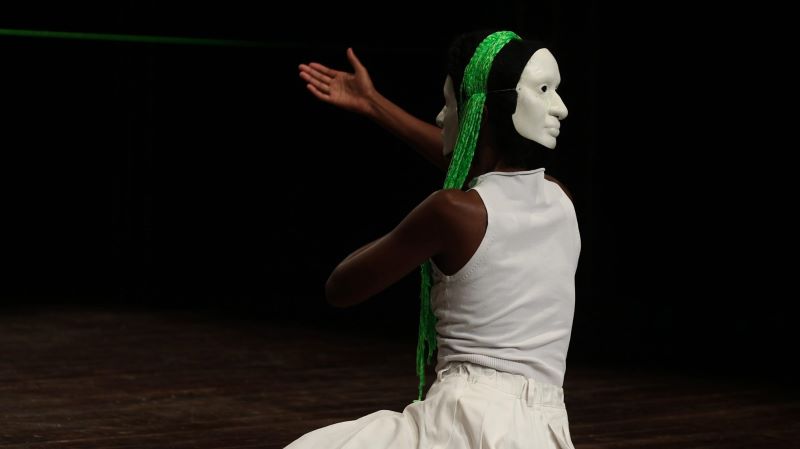

Muna Mussie in “Curva Cieca”. Photo by Archivio Muna Mussie

Il tema dell’identità sembra affiorare con forza in questo tuo ultimo lavoro: Curva Cieca. Partiamo da qui allora: chi è Muna Mussie? Come vuoi presentarti ai nostri lettori?

Adesso inizio anch’io a pronunciarlo senza accentarlo ma “Mussie” si deve pronunciare con l’accento sulla “e”! Sono nata in Eritrea e da piccolissima, nell’81, siamo venuti in Italia, perché nel mio Paese c’erano molte tensioni, dovute alla guerra di indipendenza dall’Etiopia in corso in quegli anni. Siamo arrivati in Italia grazie a mia nonna materna, che si era trasferita a Bologna negli anni ’70. Bologna è la città dove sono cresciuta e dove vivo tuttora. La mia infanzia e la mia pre-adolescenza le ho vissute in un istituto religioso. Rientravo a casa ogni tanto. Fondamentalmente, è come se dagli anni ’80 fino ai primi anni ’90 non avessi conosciuto il mondo. Sono cresciuta in un contesto molto ristretto, protetto, dove molto di quello che era all’esterno mi veniva precluso. Una volta tornata a casa definitamente per me è stato come tornare al mondo; è stata un’esplosione di informazioni, che arrivavano dalla vita quotidiana più che dalla scuola che frequentavo e che per me era molto simile all’esperienza di costrizione vissuta nell’istituto religioso.

Il rifiuto della scuola è nato dalla necessità di uscire dall’algidità e dalla freddezza di una sovrastruttura, per ritornare in una dimensione di “casa-mondo”, dove un certo calore poteva irrorare il sapere. E così, con un gesto trasgressivo, ho interrotto i miei studi al liceo scientifico. Qualche anno dopo, ho incontrato il teatro, grazie a Teatrino Clandestino, una realtà che per me è stata fonte di luce e che ha fatto riconciliare l’idea di trasgressione (il teatro è trasgressivo) con l’amore per lo studio.

Quali sono le esperienze formative che consideri rilevanti?

Le esperienze più interessanti le ho fatte al di fuori dall’istituzione scolastica. Dopo Teatrino Clandestino è stata la volta di Teatro Valdoca: prima come allieva e poi come performer e attrice per quasi un decennio. Ma la realtà che ha inciso in maniera definitiva sulle mie scelte future è stata il collettivo Open, composto tra gli altri da Cristina Rizzo e Silvia Calderoni, figure con le quali ci si è alimentate a vicenda. Open per me è stato un contenitore importantissimo, dove la pratica e la ricerca teorica andavano di pari passo: ho ricevuto un imprinting fondamentale, grazie al quale ho messo a fuoco quello che mi interessava e la mia modalità di ricerca.

Quali memorie hai conservato degli altri corpi che ha incontrato, nella danza e nel teatro?

Da bambina ho fatto un po’ di ginnastica artistica ma poi un incidente mi ha bloccata per un lungo periodo e non ho più ripreso. Sento il mio corpo decostruito: non ha un alfabeto, è sempre stato aperto e assorbente.

Con la scuola di Teatro Valdoca, certo, ho avuto insegnanti come Raffaella Giordano e Katia Della Muta, due danzatrici che mi hanno toccato profondamente. Ma sono molto legata anche a Cristina Rizzo che alla trasmissione della sua esperienza di danzatrice ha preferito l’osservazione dei nostri corpi, di quello che dicevano, per pensare insieme a noi a come questi corpi potevano parlare e muoversi in un campo libero da sovrastrutture.

“Curva Cieca” by Muna Mussie.. Photo by Archivio Muna Mussie

Mi ha colpito e sorpreso il racconto che hai fatto del tuo sofferto rapporto con la scuola, perché Curva Cieca è uno spettacolo coltissimo, che fa di te un’intellettuale a tutto tondo e nel quale, tra l’altro, il libro diventa fondamentale oggetto scenico e drammaturgico.

La scuola per me era una scomoda sovrastruttura ma questo non toglie tutta la tensione che nutro verso la scoperta e il sapere. Sono un’autodidatta. Lungi da me definirmi colta o intellettuale: sono tante le mie lacune, ed è da queste che riparto ogni volta.

Come è nato lo spettacolo Curva Cieca?

Curva Cieca è nato dall’incontro con Filmon Yemane. Il suo contributo è stato fondamentale. Io ho indicato la strada da percorrere e i punti che volevo toccare, condividendo con lui una raccolta di saggi, tratti da Corpo linguaggio e senso. Tra semiotica e filosofia [AA.VV. edito da QE, N.d.R.]. Filmon è una persona di una qualità, di un’intelligenza e di un sapere molto forti. È lui il colto: ha messo in parola le mie suggestioni.

Nell’immaginare lo spettacolo precedente – Curva– non riuscivo a vedermi concretamente sulla scena. Questo non riuscire a vedere la mia immagine è stato qualcosa di folgorante, la miccia: noi non siamo padroni della nostra immagine. Filmon Yemane è stato il mio riferimento. Lui, che ha perso la vista, fa esperienza quotidiana di questo non essere padrone della propria immagine. Quello che ho cercato di fare con Curva Cieca è stato di mettere insieme due mancanze: la mia mancanza, intuita in senso astratto e concettuale, che fa appello alla mia lingua materna (persa in tenera età) e la sua mancanza, concreta, reale della visione della propria immagine. Ho colto in queste due condizioni una formula di compensazione, la possibilità di parlare di “Immagine-linguaggio” da due prospettive differenti e paradossali -il non vedente e l’analfabeta- per tentare di far percepire la potenza che c’è in questa mancanza, attraversata dalle lezioni di tigrino che Filmon mi consegna e dal paesaggio visivo-simbolico che io intesso. È uno scambio, un gioco tra l’esperienza di perdita e quella dell’acquisizione. I corpi e le cose esistono in virtù dell’esperienza.

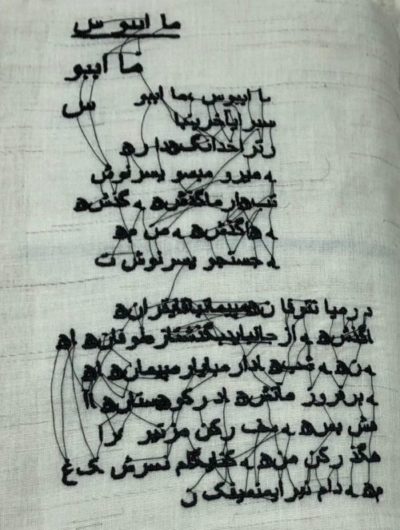

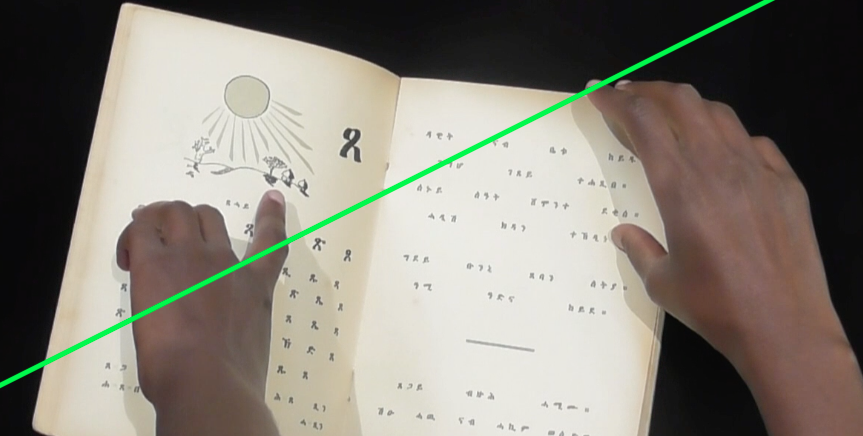

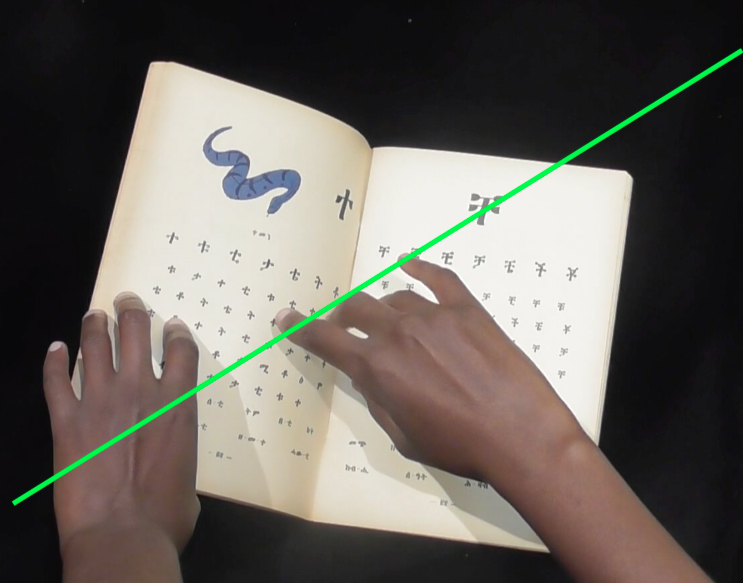

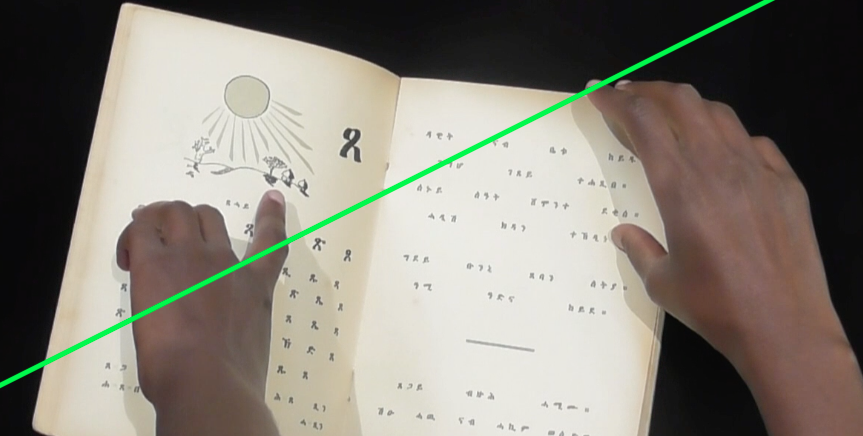

Per me la “visione” del tuo spettacolo è stata molto forte: questo filo verde teso in mezzo al palco, il video che proietta le tue mani mentre sfogliano l’abecedario in lingua tigrigna, la tua madre lingua che, per la maggior parte del pubblico si presume essere puro segno e incantamento. Grazie a quell’abecedario hai costruito una lectio magistralis, facendo di noi spettatori degli analfabeti “in ginocchio” davanti al libro, come oranti in preghiera. Il tema del linguaggio e della scrittura è un tema, tra l’altro, che hai già affrontato anche in altri lavoro: Curva ma anche FFMM (2007) e Punteggiatura, un progetto con donne straniere culminato nella creazione di una vera e propria tessitura di un libro. Insomma, nel tuo lavoro quello del linguaggio e della scrittura sono temi ricorrenti. Perché?

Il riferimento al tema della lingua materna è focale in Curva Cieca e la lingua-parola in generale è una materia creativa e creatrice che per me concorre, assieme agli altri linguaggi, a definire possibili paesaggi, punti di congiunzione e rottura tra un qua e un là; è un corpo sonoro che determina un ritmo. La mia lingua materna, persa in tenera età, continua ad esistere: c’è e non c’è e mi parla di rottura. È come il filo verde e teso in mezzo al palco, che taglia lo spazio, lo spezza, definisce un corpo d’azione; è uno snodo ma anche un punto fermo a cui reggersi nel buio. Il filo verde si posiziona simbolicamente tra il Se e l’Altro, tra un qua e un là e funge da fil rouge-verd che tiene assieme la drammaturgia.

Un giorno mia nonna mi ha regalato un abecedario della lingua tigrigna: è un oggetto di una bellezza straordinaria! Con questo abecedario ho avuto un rapporto di profondo contatto fisico. Ho sentito da subito la necessità di toccare le parole e di guardarlo, di sfogliarlo e risfogliarlo. Le mie mani in video che sfogliano l’abbecedario sono il medium tra il corpo libro, il corpo scenico e il corpo spettatore. Sulla scena gravitano diversi piani linguistici, c’è una continua trasmissione di sapere. Per parlare di quell’abecedario, ad esempio, ho dovuto informare Filmon che in quella determinata pagina c’è quella precisa immagine, immagine che nella sua testa può essere trascritta in tutt’altro modo.

Questo è l’interessante per me: avere sempre una linea di margine che non potrò mai varcare. Io non potrò mai sapere come lui “vede” quell’immagine e lo stesso vale per lui nei miei confronti. Mi diverte pensare alla mia pratica come ad una scienza di confine, che sta tra la razionalità del sapere e l’ignoto al quale ognuno di noi appartiene. L’ignoto è come una scissione che ci portiamo dentro dal momento in cui siamo entrati nel linguaggio. Prima di questa scissione c’è una “sensibilità”, che continua ad attraversare e informare a sua volta il linguaggio. In questo insistente tentativo di spiegarsi, si interroga sempre qualcuno o qualcos’altro da sé: è in questo interrogare

che si diventa già altro da sé.

Ritratto di Muna Mussie. Photo by Monia Ben Hamoudia

Ascoltandoti mi viene in mente l’espressione: “diritto all’opacità”. Ho letto Auto-défense psychédélique-il bel testo che Simone Frangi ha scritto su di te. In un passo iniziale, citando Elsa Dorlin, dice: “Muna Mussie aderisce a questa scienza vitale dell’autodifesa […] un istinto permanente di conservazione contro la violenza, elemento strutturale del patriarcato e del capitalismo”. Che cosa ne pensi? Sei d’accordo?

Apprezzo molto il lavoro e la ricerca di Simone, anche se il testo che hai citato è per me un po’ violento. Sicuramente dice delle verità ma quello che cerco di fare io è di situarmi in una zona un po’ più sottile. A me interessa l’essere, a prescindere dalle provenienze e dai colori che porta. Certamente sono responsabile di quello che io di primo acchito rappresento. Devo tenerne conto, non posso fingere di non essere nera, di non appartenere ad una storia tragica (anche se la Storia è tutta tragica). La mia responsabilità è quella di lavorare sull’immaginario, avvicinando tematiche che vogliono decolonizzarlo. Ma non lo faccio in modo ideologico. Credo che l’immaginario debba restare libero da certe definizioni e connotazioni. Soprattutto sto attenta a come parlare di certe tematiche perché non mi interessa produrre nuove forme di vittimismo: è un rischio che bisogna evitare se non si vuole continuare a reiterare una certa violenza.

Ci sono artisti -ed io probabilmente sono tra questi – che sono tenuti ad attraversare loro malgrado queste tematiche. Ma il mio timore è che, se il linguaggio di un artista si piega e si mette a servizio di queste tematiche, quando l’interesse verso di esse svanirà, allora non rimarrà più nulla a quest’artista. Attingere dal mio vissuto, dal mio privato è solo un movente per parlare di qualcosa d’altro, per parlare non di me ma dell’essere, che non è più “io” ma qualcosa di così profondamente personale da essere anonimo.

L’opacità di cui parli per me è l’opacità dell’essere. Dobbiamo uscire dalle categorie e questo tentativo di uscita crea opacità. Mi rifiuto di essere definita, questo sì. La ricerca dell’identità non è la ricerca delle radici. È un interrogarsi costante su chi siamo adesso, in questo istante transitorio.

“Curva Cieca” di Muna Mussie. Photo by Archivio Muna Mussie

In scena tu “danzi” le lettere dell’alfabeto tigrino.

I segni dell’alfabeto tigrino per me sono come una coreografia innata, che non ho impostato io. Cercare di danzarli è come cercare di danzare un albero: i miei occhi cercano un albero, lo vedono e il mio corpo cerca di seguire quell’albero. È una coreografia naturale, già data. L’alfabeto tigrino è un segno, che cerco di seguire, di attraversare con il mio corpo. Ma, ogni volta che io cerco di aderire a quel segno, nel mio corpo succede qualcosa di diverso. avviene un passaggio di trasmissione sempre differente: una mutazione. Questo mi permettere di mantenere sempre una tensione tra il corpo e la visione.

Muna Mussie in “Curva Cieca”. Photo by Archivio Muna Mussie

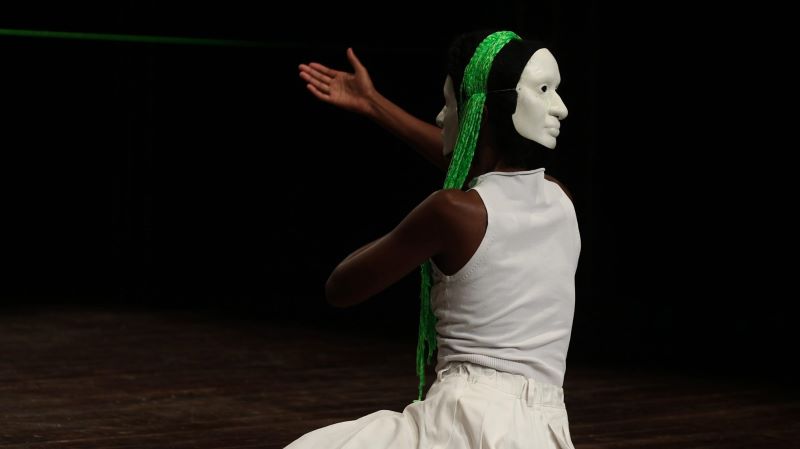

In Curva Cieca indossi una maschera. Ci racconti perché?

La maschera bianca che indosso è un calco in 3D del mio volto. Il fatto che sia di colore bianco a qualcuno forse può aprire a delle suggestioni legate al colore della pelle. Può far pensare ad esempio a Pelle nera, maschere bianche [il libro di Franz Fanon (1952) nel quale l’autore si interroga sui meccanismi di oppressione psicologica e politica esercitati sulle persone di pelle nera, N.d.R.]. Oppure può far pensare allo scimmiottare il blackface [forma teatrale con la quale gli attori di pelle bianca si truccavano il viso per sembrare di pelle nera, perlopiù a scopo caricaturale e denigratorio] attraverso il witheface [forma teatrale in cui ci si trucca per apparire di carnagione bianca, N.d.R.].

Ma più di tutto per me il colore bianco della maschera è il bianco di un foglio, dove poter scrivere una storia. Ad un certo punto, infatti, traccio dei segni sulla maschera, come nel linguaggio dei cavernicoli e la maschera diventa mezza bianca e mezza nera. La maschera che uso, tra l’altro, è una maschera bifronte come Giano che, secondo il mito, può guardare al futuro e al passato simultaneamente. A me, in scena, questa doppia maschera permette simultaneamente di mantenere un contatto visivo con il video del libro proiettato sul fondale e un rapporto di contatto con lo spettatore. Questa maschera compie una sorta di viaggio circolare e, nell’accostarsi di volta in volta ad altri piani linguistici, diventa ogni volta qualcos’altro.

Nei miei lavori tento di innescare dei piccoli cortocircuiti percepibili e impercettibili, attraverso i quali cerco di portare in un altro luogo. Cerco di creare dei “campi di gioco” per la diacriticità, per le singolarità e di creare degli scarti; cerco di creare una struttura fluttuante.

Dove si colloca l’altrove di cui parli?

È quella linea di confine, quella rottura dei codici, necessaria per muoversi e avanzare. È la scissione che ognuno porta dentro di sé, un’alterità introiettata che spaventa e nutre allo stesso tempo.

Non so spiegare il perché ma una delle cose che mi sono ostinatamente chiesta dopo aver visto il tuo spettacolo è perché il filo teso sul palco è proprio di quel colore: verde.

Mi piace il verde, è un colore che calma, è il colore della natura, è riposante, è un colore amico dell’uomo e in questo senso è anche un canale caldo per me. Certo, poi la mia scelta è dovuta anche al fatto che in scena il verde fa gioco agli altri livelli cromatici: il bianco e il nero. Ma, fondamentalmente, l’ho scelto perché è un colore legato alla natura. Il nostro primo apprendimento avviene attraverso gli elementi della natura, la natura è la casa: la foglia, l’animale… Nell’abbecedario di mia nonna ci sono molti riferimenti alla natura. Ci sono molti animali, ad esempio, e l’animale porta sempre in un altrove, in un altro luogo: l’animale ha già un suo linguaggio, un suo territorio. Ecco: Curva Cieca è un viaggio su più piani, che non è organizzato in modo gerarchico, c’è una orizzontalità e una simultaneità dei piani, una convivenza intima tra concettualità ed emotività.

Anna Trevisan

Foto di copertina di Monia Ben Hamoudia

English version

Muna Mussie Interview | The green thread of nostalgia

Muna Mussie enters the Zoom interview, wearing a green sweatshirt and congenial smile. She grins when I say her name and tactfully corrects me. She listens keenly to my questions and interlaced her answers with boundless patience, gradually leading me inside her world, populated by objects, memories and connections where past, present and future are interlinked circles. I occasionally felt rather out of my depth during the conversation, which entwined the deepest depths of emotional intensity with the highest peaks of cultural refinement. It was as if my eyes were guided by invisible fingers, somehow indicating other directions, other answers. Muna unravels and re-stitches our discourse a thousand times, inserting pauses, digressions, fresh starts, threads which might lead somewhere else entirely. This interview is a four-handed tapestry, of warp and weft, interviewee and interviewer, a weaving of words together.

Muna Mussie in “Curva Cieca”. Photo by Muna Mussie Archive

The theme of identity seems to crop up a lot in your latest work: Curva Cieca. So let me turn the tables: who is Muna Mussie? How do you want to introduce yourself to our readers?

Now even I’m starting to echo how others say it, but really it ought to be pronounced “Mussié” with the stress on the final “e”!

I was born in Eritrea and when I was very young, in 1981, we came to Italy, because of the tense situation there. There was the ongoing war of independence from Ethiopia at that time. We settled in Italy thanks to my maternal grandmother, who had moved to Bologna in the 1970s. Bologna is the city where I grew up and where I still live.

I spent my childhood and pre-adolescence in a religious institute. I only went back home occasionally. Basically, from the 1980s until the early 1990s it was as if I had not known the world. I grew up in a very restricted, protected context, where much of what was outside was closed-off to me.

When I returned home it was like coming back to the real world; it was an explosion of information, which came from everyday life rather than from the school that I then attended which was, for me, very similar to my experience of constraint in the previous religious institute.

My rejection of school was driven by my wish to break free from the rigid coldness of a superstructure, to return to a “home-world” dimension, where a certain coziness could perfuse learning. And so, in a transgressive gesture, I discontinued my studies at the scientific high school. Then a few years later I chanced upon the realm of theatre, thanks to Teatrino Clandestino, a reality that for me was a source of light, allowing me to reconcile the idea of transgression (theatre is transgressive) with my love of studying.

What formative experiences do you consider relevant?

The most stimulating experiences I have had were all external to school. After Teatrino Clandestino it was the turn of Teatro Valdoca: first as a student and then as performer and actor for almost a decade. But the thing that definitively impacted my future choices was Open, a collective composed by, among others, Cristina Rizzo and Silvia Calderoni, figures who nourished each other. For me Open was a container, one of great value, where practice and theoretical research went hand in hand: I gained an imprinting that was fundamental, and from which I was able to really focused on what interested me as well as my research method towards that goal.

What memories have you kept of the other bodies you met, in dance and theatre?

As a child I did a little bit of artistic gymnastics but then an accident prevented be from carrying on for a long period and so I never really took it up again. My body feels deconstructed: it has no alphabet of its own, it has always been open and absorbing.

With Valdoca’s theatre school, of course, I had teachers like Raffaella Giordano and Katia Della Muta, two dancers who touched me deeply. But I’m also very attached to Cristina Rizzo who preferred to accentuate the observation of our bodies, of what they said, to the transmission of her experience as a dancer and, along with us, consider how these bodies could speak and move in a sphere free from superstructures.

“Curva Cieca” by Muna Mussie. Photo by Muna Mussie Archive

I was struck earlier by your strained relationship with school, rather taken aback, because Curva Cieca is a highly cultured show, which makes you an all-round intellectual and in which, among other things, the book becomes a fundamental dramaturgical prop.

School for me was an uncomfortable superstructure but it didn’t sap away all the impetus I had towards discovery and knowledge. I’m self-taught. Far be it from me to define myself as cultured or intellectual: there are many gaps, and it’s from these lacunas that I strike out every time.

How was the show Curva Cieca (Blind Curve) born?

Curva Cieca grew out of a meeting with Filmon Yemane. His contribution was indispensable. I had indicated the way to go and the points I wanted to cover, sharing with him a collection of essays, taken from Corpo linguaggio: tra semiotica e filosofia e senso [(body language: between semiotics, philosophy and sense) by Prisca Amoroso et al, published (in Italian only) by Società Editrice Esculapio in 2020]. Filmon is an impressive character, highly intelligent and knowledgeable. Creative too: he transformed my mere suggestions into words.

In imagining the show – Curva – I couldn’t actually envision myself on the stage. This inability of mine to view my own image was somewhat startling, yet also a fuse: we are not masters of our own image. Filmon Yemane was my reference. He, who had lost his sight, experiences this lack of control over his own image every day. What I tried to do with Curva Cieca was to splice together two shortcomings: my absence, perceived in an abstract and conceptual sense, which applies to my mother tongue (which I had set aside in early childhood), and the concrete, real lack of vision of one’s own image. In these two conditions I used a formula for compensation, the possibility of speaking of “Image-language” from two distinct and paradoxical perspectives – the blind and the illiterate – to try to make people perceive the potentiality that endures in this deficit, through the Tigrinya language lessons that Filmon gives me and the visual-symbolic landscape that I weave. It is an exchange, a game between suffering loss and experiencing acquisition. Bodies and things exist by virtue of experience.

For me, your show’s visuals were very strong: this green thread stretched across the middle of the stage, the video that projects your hands leafing through a Tigrinya book of the alphabet, your mother tongue which for most of the audience would be seen as symbols of enchantment. By showing us these “A–B–Cs” you have created a lectio magistralis, making us illiterate spectators “kneeling” in front of the book, as if in prayer. You have already addressed the theme of language and writing in your other pieces: not only Curva but also FFMM (2007) and Punteggiatura, a project involving immigrant women which culminated in the woven creation of an actual book. In short, language and writing are recurring strands in your work. Why?

Reference to a mother tongue is a central theme in Curva Cieca, as is language-word in general. It is innovatory matter which is also constructive, for me it contributes, together with other languages, to define conceivable landscapes, points of conjunction and rupture between a here and a there; it is a body of sound that determines a rhythm. My mother tongue, which wilted in me at an early age, continues to exist: it’s both there and not there, it speaks to me of rupture. It’s like the green thread stretched across the middle of the stage, cutting space, fracturing it, delineating a body of action; it is an articulation yet also a fixed point to hold onto in the dark. The green twine is located symbolically between the Self and the Other, between a here and a there.

One day my grandmother gave me a Tigrinya alphabet book: it’s an object of extraordinary beauty. With this manual to the A–B–Cs I attained a relationship of intense physical contact. I immediately felt the need to touch each letter and admire them, to thumb through it repeatedly. My fingers in the video, leafing through that alphabet, represent the medium between the body of the book, the body on stage and the body of spectators. Different linguistic levels bear down on the scene, there is a continuous transmission of knowledge. To talk about that alphabet book, for example, I had to tell Filmon that on any particular page there is a precise image, an image that could be transcribed in his mind’s eye in a completely different way.

This is what is interesting for me: always having a line down the margin that I’ll never be able to cross. I will never know how he “sees” that image and the same goes for him towards what I see. I enjoy thinking of my practice as a border science, which lies between the rationality of knowledge and the unknown to which we all find ourselves. The unknown is like a fissure, one that sunders us from the moment we enter language. Before this split there is a “sensitivity”, which continues to intersect and inform language in turn. In our insistent attempt to explain ourselves, we always interrogate someone or something other than ourselves: it’s via this passage that we already become something other than ourselves.

Muna Mussie. Photo by Monia Ben Hamoudia

Listening to you, a phrase comes to mind: “right to opacity”. I read Auto-défense psychédélique, the delightful paper that Simone Frangi wrote about you. In the initial paragraph, quoting Elsa Dorlin, he writes: “Muna Mussie adheres to this vital science of self-defence […] a permanent instinct for self-preservation against violence, ‘a structuring element of patriarchy and capitalism’”. What do you think? Do you agree?

I really appreciate Simone’s work and research, even if the passage you quoted is a little intemperate for my taste. It certainly tells the truth, but what I try to do is to situate myself in a slightly more subtle area. I am interested in being, regardless of its origin or colour. I‘m certainly responsible for what I represent at first glance. I have to take this into account, I can’t pretend to be non-black, to not belong to a tragic history (even if all of history is tragic). My responsibility is to work on the imaginary, approaching issues with a view to decolonize. But I don’t carry it out in an ideological way. I believe that the imagination must remain free from certain definitions and connotations. Above all, I’m careful about how I talk about certain issues because I’m not interested in producing new forms of victimhood: it’s a risk that must be avoided if you don’t want to continue repeating certain forms of violence.

There are artists – and I am probably one of them – who are bound to address these issues in spite of themselves. But my fear is that, if the language of an artist compromises and puts themselves at the service of these frictions, when the interest wanes, then there’ll be nothing left for this artist. Drawing from my experience, from my private life, is a way to talk about something else, not about myself but about being, which is no longer “I” but something so deeply personal as to be anonymous.

The opacity that you quoted is the opacity of being. We have to get out of categories and this attempt to escape them creates opacity. I refuse to be defined, yes. The search for identity is not the search for roots. It is a constant questioning of who we are now, in this transitory moment.

On stage you “dance” the letters of the Tigrinya alphabet

For me the characters of the Tigrinya alphabet are like an innate choreography, one which I didn’t set up. Trying to dance them is like trying to dance a tree: I’m looking around for a tree, my eyes see one and my body tries to supplant that tree. It’s a natural choreography, already given. Each letter of the Tigrinya alphabet is a grapheme that I try to follow, to integrate with my body. But, every time I try to adhere to that symbol, something different happens in my body, a different passage of transmission always takes place: a mutation. This allows me to continually maintain a tension between body and vision.

Muna Mussie in “Curva Cieca”. Photo by Muna Mussie Archive

In Curva Cieca you wear a mask. Can you tell us why?

The white mask I’m wearing is a 3D cast of my face. The fact that it is white may allude to my black skin in the minds of some. For instance it may bring to mind Black Skin, White Masks [by Franz Fanon (1952) in which the author scrutinises the mechanisms of psychological and political oppression exercised on black people, Ed.]. Or it could hint at blackface through whiteface.

But, above all for me, the whiteness of the mask is the whiteness of a fresh sheet of paper, onto which a story may be written. Indeed, at a certain point I even draw marks on the mask, a sort of cavemen language, then the mask becomes half white and half black. The mask I use, among other things, is two-faced, like the Janus myth, it can look to the future and past simultaneously. On stage this double mask allows me to simultaneously keep visual contact with the video of the book on the backdrop whilst still maintaining “eye contact” with the audience. This mask makes a sort of circular journey and, ascending towards other linguistic levels, becomes something different every time.

In my works I try to trigger small perceptible or imperceptible short circuits, through which I try to lead on to another place. I try to create “playing fields” for diacritics, for singularities and to generate throw-aways; I aim for a floating, fluctuating structure.

Where is that elsewhere you speak of?

It’s that borderline, that breaking of codes, necessary to move and advance. It’s the bifurcation that everyone carries within themselves, an introjected otherness that frightens and nourishes at the same time.

I can’t adequately account for it but, after seeing your show, there was a curiosity that I couldn’t dislodge from my mind. It centred upon one aspect of that thread which stretched across the stage. Why that one colour: green?

I like green, it’s a colour that calms, it’s nature’s hue, it’s restful, it’s a human-friendly colour and for these reasons it’s a favourite of mine. My choice is also due to the fact that green plays well on stage with the other tones of course: black and white. Basically I just chose it because it’s the tint most affiliated with nature. Our first learning takes place through natural elements, nature is our home: leaves, animals… In my grandmother’s alphabet book there’s an abundance of references to nature. Many animals, for instance, and those animal always leads to somewhere else, to another domain: an animal already has its own language, its own territory. So, to sum up: Curva Cieca is a journey on several levels, which is not organised in a hierarchical way, there is both a horizontality and simultaneity of these levels, an intimate coexistence between conceptuality and emotionality.

Anna Trevisan

English translation by Jim Sunderland

Cover image by Monia Ben Hamoudia

Aggiornato e modificato il 13/09/2021 ore 11.25

Tags: Boarding Pass Plus, Muna Mussie