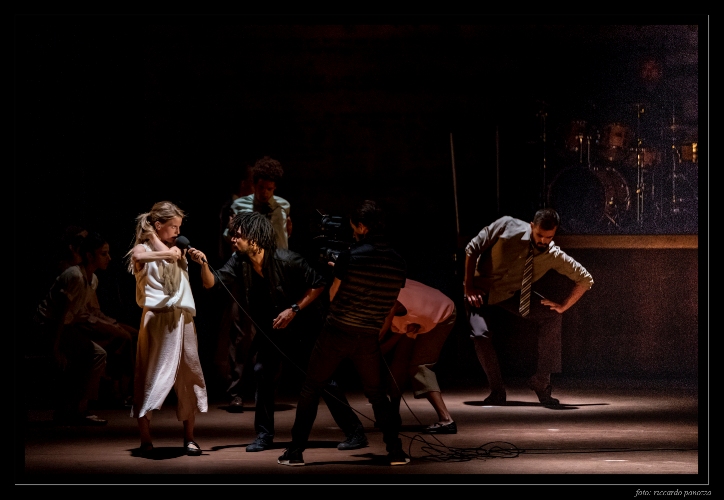

28 luglio 2018, Operaestate Festival, Castello degli Ezzelini, Bassano del Grappa |

ENG | Here is our review of Goat by Ben Duke with Rambert Dance Company , performed in Castello degli Ezzelini, Bassano del Grappa, Italy. Enjoy!

ITA | Qui di seguito la nostra recensione dello spettacolo Goat di Ben Duke interpretato dalla Rambert Dance Company.

IL TESTO ITALIANO È DISPONIBILE DI SEGUITO A QUELLO INGLESE

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

“But what happened, Miss Simone? Specifically, what happened to your big eyes that quickly veil to hide the loneliness? To your voice that has so little tenderness, yet flows with your commitment to the battle of Life? What happened to you?”. It was with such anguish that the extraordinary African-American poet Maya Angelou wrote about the much cherished Nina Simone back in 1970.

But what happened to the dance? Specifically, what happened to us as distracted spectators, our big eyes drawn towards the video screen, preferring it over the reality of living bodies. What happened to our gaze, unable to see real life, all of us too absorbed by the bubbling inside the tremendous cauldron which is the media’s reality show? To our “civilisation”, besieged and under attack, which dialectically devours itself? Today one could perhaps paraphrase the words of Maya Angelou (awkwardly and indecorously), to ask the same questions of Goat; an original and unsettling performance from choreographer Ben Duke, played impeccably by the Rambert Dance Company.

At the dramaturgical heart of the production is the theme of sacrifice, formally inspired by Stravinsky’s renowned The Rite of Spring. The sacrificial girl is condemned to dance herself to death, thus assuring the return of Spring. But here gender codes are reversed: a girl isn’t relinquished, but a boy. He is helpless and maybe unaware of being the prosopopoeia of dance, perhaps even our own civilisation which is sacrificed to propitiate the end of cultural barbarism, and much besides: indeed all that which we have voted for — hollowly.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

In fact, the sacrificial theme is hinted at by the piece’s title — Goat — not much of a stretch to the substantive scapegoat. The actual sacrifice scene is riddled by a hail of fragments and splinters from contemporary culture, and is perpetrated within the voluptuously melancholic, necessarily intense and dazzling notes of Nina Simone’s songs. Moreover, the show’s soundtrack is delivered by way of one of the most beautiful and powerful voices in world culture, but above all an African-American voice, instantly creates a semantic short circuit which multiplies and amplifies the meaning of the representation. The echo of slavery and the breaking of black American slaves permeates the weave of the dramaturgical fabric, producing a wider movement, a broader wave, which rolls and rails against the universal boundaries of civil rights, freedom, equality and, by contrast, their denial. Who more than the blacks of America have been the scapegoats of a burgeoning United States? Who more than American blacks have been so repressed in Western culture, its roots sinking deep into unutterable factuality?

But nothing is didactic, nothing is pathetic in this mock educational show, one that contrives a spurious allure. The strains of Nina Simone open up a dark yet starlit passage through the night of despair, overcome every temptation toward stereotypical portentousness thanks to Nia Lynn’s intense live vocal interpretation and with Yshani Perinpanayagam at the piano.

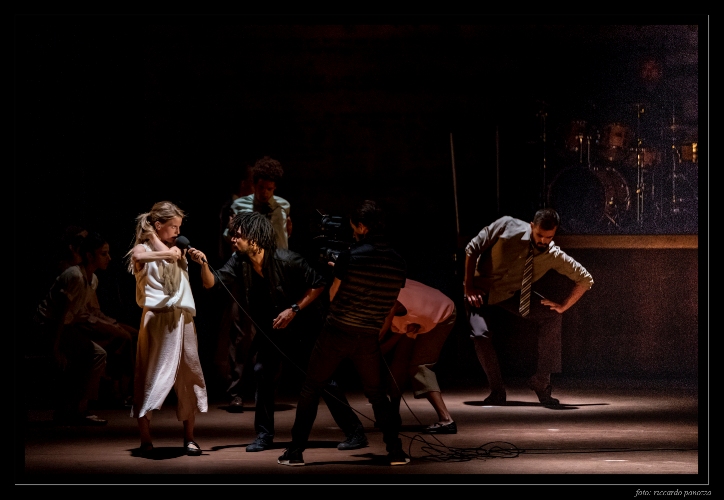

The astonishing launch of the television warm-up act, transforms the opening of the show into something of a starched and premeditated atmosphere, a “something” to which the rituals of the television age have accustomed us to. A sort of “he who excuses himself, accuses himself”, a directorial note to justify/prepare/accompany the transformation of the Rambert Ballet’s principle dancer into a consummate anchorman and petulant invasive journalist. He is accompanied by a diligent video-maker who constantly transmits whatever action occurs, a live link to the monitor on the edge of the stage. The presenter/journalist slavishly and unduly gives a running commentary on everything that happens on stage, in that incessantly irritating telecaster’s style. Finally, on the well-known opening bars of Feeling Good, it all flips. At last the dancers dance, revealing the structure of the show in a breathtaking balance between choreography, entertainment, theatre, TV news, live concert, theatrical aims and poetical attestation.

“It’s a new dawn / It’s a new day / It’s a new life for me / And I’m feeling good”.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

The blue voice of Nina Simone still pierces bitter and deep through the vocalisation of Nia Lynn, passing on to us the sacred fire of the naked truth. Not whatever truth, not that daughter of the conservatoire, but one born out of smoke-filled sordid dives, between the sensual cords of a double bass and the jazzy tintinnabulation up and down a piano’s ivories. A truth that is not synonymous with civilisation but its extreme opposite, and against which it fatally collides. In this collision it is civilisation that crumbles and ends up on the ground like pale dust, while the truth is buried alive, under the rubble.

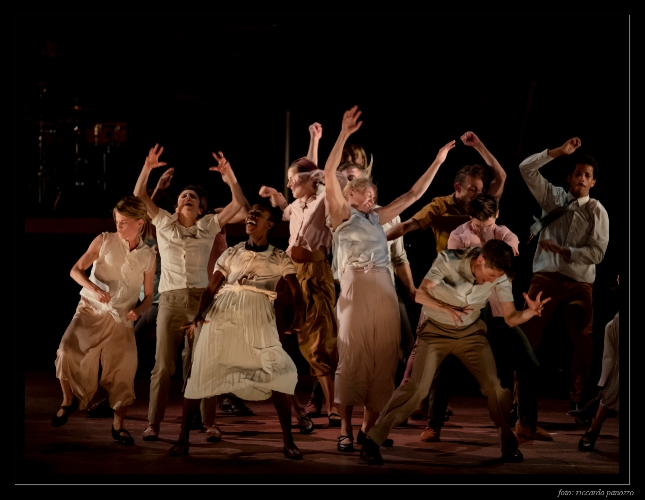

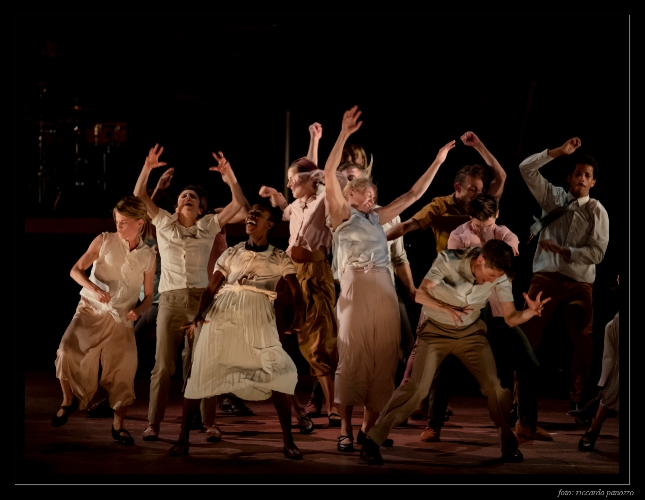

They sway like a tragic chorus, withered by time; they dance like ghosts. They cavort like those dissolute and sweaty bodies found in back-alley dance halls, for blacks only; they dance in protest and pride, with the conviction and despair of the first freedom marches against racial segregation; they dance with joy and hope, as if to a glorious gospel choir. A pile of bodies, expressive and emphatically contemporary, all in pastel colours, shades of the 1950s.

The umpteenth pedant commentary of that journalist generates an unbearable shrillness, an interference that collides and clashes with the poetic beauty of the music and the dance. The mainstream media’s prattle sounds superfluous and disturbing, it confuses — intentionally, we’re sure — while we listening and watch it. The small TV on the stage continues to broadcast the cameraman’s coverage. The resultant mise en scène somewhat alludes to Goya’s Las Meninas, but with a twist: the representation of a representation is not revealing, this is because it jettisons the fundamental feeling of empathy, enticing us to believe what they want us to feel rather than what we actually feel.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

“What is your dance about?” The anchorman asks insistently to all the dancers on stage, unmasking the unbearable banality of the news, of its information, of its interpretation; exposing the stinging effect of this seeking an immediate meaning, promised by TV and media, without any digestion, bereft of any reflection, devoid of any effort. The meta-dramaturgical text intelligently wraps itself underneath the hearth of the show, making us question what dance means for us, whilst we watch and refract the question onto the dancers themselves. A piece that is a real puzzle, a charade, a reflecting prism of lights and colours, all in constant motion. “Addiction”, “betrayal”, “justice” — reply the grilled dancers, providing us with a feeble trace, along with the false trail of comedy which derides the audience with an all too easy and auto-ironic mockery of language, that of contemporary dance, which often risks being self-referential.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

Upon those angry notes of Ain’t Got No the chorus of dancers turn back to the undisputed protagonist, with a group gesture that seems spiritual, which ends with their hands waving high in the air, as if expressing a hallelujah. Until the journalist/anchorman breaks in again to continue his unsettling pursuit, with his wink towards the audience: “Okay audience, the woman in the middle is Fate”. Then a representation of profane love made sacred by death is enacted. She is Hanna, pale and blonde; he is Liam, with swarthy features and dark skin. They love each other, but Fate separates them, condemning him to ritual death. The scapegoat has been identified. The ritual can begin. The reality show will be broadcast live. “Liam, you’ve been chosen. Wow!” Announces the journalist. Then the reporter asks enthusiastically: “You must be very excited… what have you been chosen for?”, “I’ve been selected to be sacrificed” — Liam replies. “Could you describe your feelings?”— the reporter enquires insistently. “I have to dance myself to death” rejoins Liam. The sacrificial ritual seems to increasingly take on the contours of an ancestral dance, of the timeless vanquished, of every latitude, who rebel against destiny, captured and then immolated. The dancers tighten around the chosen one, forming a ritual circle that pulsates to the beat of the drum. The chosen one remains still, on his knees, awaiting whilst a climax of voices rises in the air. The sacrifice has begun. The half-naked body of the chosen one is suffused in yellow post-it notes, making him a reluctant bearer of illegible and hence indecipherable messages.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

The poignant words of My Way accompany the kneeling chosen one, waiting while the dancers line-up in a row, clicking their fingers in rhythm, barefoot, in pastel clothes which now vaguely evoke the ‘70s and ‘80s. Next a dancer rushes the stage and brusquely interrupts the singer, whilst she is still on-air and being broadcast. The sacrifice can wait — “What is a man, what has he got? / If not himself, then he has not / To say the things he truly feels / Not words of one who kneels / And that shows I took the blows / And did it my way!” — bawls the dancer until the singer resumes her song and the dancers snap their fingers again.

The Ballad Of Hollis Brown marks the beginning of the condemned man’s death dance, one of the most powerful moments in the show. The sacrificial victim rotates his arms, which suddenly seem gigantic, enormous, infinite. He steers his body with movements from his sternum, rotating his forearms to the compulsive and repetitive rhythm. His strenuous ride on the spot is powerfully dramatic. His mortal dance stretches his arms into a marvellous and powerful stroke, and he swims in infinite arcs. Then, he falls to the ground exhausted, under destiny’s yoke of love and death to which he has been summoned. “Ladies and gentlemen, there is a man on the floor and his breathing is getting shallower” the journalist proclaims.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

The lovely Hannah mourns the death of her Liam. Emptiness, loss, void, despair dance along with the song, while the couple engage in a movingly macabre dance, a stormy fight of clinches, yielding and collapsing, seizures and chases. The watercolour impressions of the dancers is juxtaposed with the scathing pop cartoon of the presenter, as well as the blue velvety soundtrack. The real embrace of the pair of lovers on stage — Hannah and Liam — merges with the virtual embrace broadcast by way of the TV monitor. Actuality is confused with the on-screen reality show and feelings suffer under the feral stalking carried out by the obligation of news to (so-called) inform, in which the proximity of the camera to the dancers’ bodies is likely to destroy any authenticity of empathy.

How do we feel, us the audience, at the end of the show? “Feelings, nothing more than feelings”. Impotence, despair, feeling dazed and at the same time sordid, a rebellious hope further fuelled by an ambiguous coupe de theatre that closes the show, and does so in a surprising way.

Text by Anna Trevisan

Translation by Jim Sunderland

Photos: Courtesy of Riccardo Panozzo

TESTO ITALIANO

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

“But what happened, Miss Simone? Specifically, what happened to your big eyes that quickly veil to hide the loneliness? To your voice that has so little tenderness, yet flows with your commitment to the battle of Life? What happened to you?”. Così scriveva accorata nel 1970 la straordinaria poetessa e scrittrice afroamericana Maya Angelou a proposito dell’amatissima Nina Simone.

Ma che cosa è successo alla danza? In particolare, che cosa è successo ai nostri occhi di spettatori ormai distratti, che corrono subito al video, preferendolo alla realtà dei corpi. Che cosa è successo al nostro sguardo, incapace di vedere la vita reale, troppo assorto a guardarla nel grande calderone del reality show mediatico e televisivo? Alla nostra “Civiltà”, sotto attacco e assediata, che dialetticamente divora se stessa? Così oggi, si potrebbero forse (maldestramente e impropriamente) parafrasare le parole di Maya Angelou, per interrogare l’originale e spiazzante spettacolo Goat del coreografo Ben Duke, interpretato dagli impeccabili danzatori della Rambert Dance Company.

Il cuore drammaturgico dello spettacolo è il tema del sacrificio, formalmente ispirato a quello celeberrimo de Le sacre du printemps di Stravinskij, che condanna la fanciulla a danzare fino alla morte per far tornare la Primavera. Ma i codici di genere sono invertiti: a morire non è una fanciulla ma un ragazzo, inerme e ignaro di essere, forse, la prosopopea della danza e forse della nostra stessa Civiltà, sacrificata per propiziare la fine della barbarie culturale, e non solo, cui ci siamo cupamente votati.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

In effetti, il tema del rito sacrificale si lascia cripticamente annunciare già dal titolo -“Goat”, “capro”- che sembra sottintendere il più rivelatore “Scapegoat”, “capro espiatorio”. Il sacrificio scenico è trafitto da una miriade di frammenti e di schegge del contemporaneo, e si consuma dentro le note voluttuosamente tristi, necessariamente intense ed abbacinanti delle canzoni di Nina Simone. E che la musica dello spettacolo sia consegnata ad una delle voci più belle e potenti della cultura mondiale, ma anche e prima di tutto afroamericana, crea subito un cortocircuito semantico, che moltiplica e amplifica il significato della rappresentazione. L’eco della schiavitù e del supplizio degli schiavi e dei neri d’America si infiltra nel tessuto drammaturgico, producendo un movimento più ampio, un’onda più vasta, che lambisce i confini universali dei diritti civili, della libertà, dell’uguaglianza e, per contrasto, della loro negazione. Chi più dei neri d’America è stato il capro espiatorio del successo americano? Chi più dei neri d’America è stato il grande rimosso della cultura occidentale, le cui radici profonde affondano in fatti indicibili?

Ma nulla è didascalico, nulla è patetico in questo spettacolo fintamente didattico, fintamente ammiccante. E le canzoni di Nina Simone, che aprono un varco buio e stellato insieme nella notte della disperazione, sopravvivono ad ogni tentazione di stereotipata retorica grazie all’intensa interpretazione dal vivo di Nia Lynn alla voce e di Yshani Perinpanayagam al pianoforte.

Lo spiazzante inizio da avanspettacolo televisivo, trasforma l’apertura dello spettacolo in qualcosa dal sapore inamidato e poco spontaneo, un “qualcosa” al quale ci hanno abituato i rituali e i tempi televisivi. Una sorta di “excusatio non petita”, una nota di regia per giustificare/preparare/accompagnare la trasformazione del primo ballerino della Rambert Ballet in anchorman consumato e in petulante giornalista d’assalto, accompagnato da un solerte video maker che, per tutto il tempo, riprende quanto accade sul palco, trasmettendolo in diretta dal monitor collocato a bordo palco. Il presentatore/giornalista commenta pedissequamente ed inutilmente tutto quanto accade in scena, con uno stile odiosamente televisivo-giornalistico. Finalmente, si interrompe, sulle note della celeberrima Feeling good. Finalmente, i ballerini danzano, rivelando la struttura dello spettacolo, in mirabolante equilibrio tra scena coreutica, intrattenimento, teatro, cronaca TV, concerto dal vivo, meta teatro e dichiarazione di poetica.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

“It’s a new dawn / It’s a new day / It’s a new life for me / And I’m feeling good”.

La voce blu di Nina Simone trapassa amara e profonda attraverso quella di Nia Lynn, porgendoci il fuoco sacro della nuda verità. Non una verità qualsiasi, non quella figlia della scolarizzazione ma quella nata dall’odore di sigarette in sordidi locali, tra le corde sensuali di un contrabbasso e i tasti di un pianoforte percosso da musica jazz. Una verità che non è sinonimo di civilizzazione ma che ne è piuttosto il suo acerrimo contrario, e contro il quale, fatalmente, collide. Nella collisione, è la civiltà a sbriciolarsi e a finire a terra come pallida polvere, mentre la verità viene seppellita viva, sotto le macerie.

Ballano come un coro tragico, avvizzito dal tempo, i danzatori; ballano come spettri. Ballano come i corpi licenziosi e sudati delle balere segrete, per soli neri; ballano per protesta e per orgoglio, con la convinzione e la disperazione delle prime marce contro la segregazione razziale; ballano di gioia e di speranza, come durante le gloriose messe gospel. Un grumo di corpi espressivi e terribilmente contemporanei, in una mise color pastello che evoca vagamente gli anni ’50.

L’ennesimo commento pedante del giornalista produce uno stridore insopportabile, un’interferenza che urta e si scontra con la bellezza e la poesia della musica e della danza. La parola mediatizzata suona superflua e disturbante, confonde – ne siamo certi, intenzionalmente- l’ascolto e la visione. La piccola Tv a bordo palco continua a proiettare le immagini riprese dal cameraman. Il risultato compositivo complessivo sembra citare Las Meninas di Goya ma con esito rovesciato: la rappresentazione della rappresentazione non è rivelatrice, perché spezza il fondamentale sentimento dell’empatia, invitandoci a credere non a ciò che realmente sentiamo ma a ciò che vogliono farci sentire.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

“What is your dance about?” chiede insistente l’anchorman a tutti i ballerini in scena, smascherando l’insopportabile banalità della cronaca, dell’informazione, dell’interpretazione; smascherando l’effetto urticante della ricerca di senso immediata, promessa dalla TV e dai media, senza alcuna digestione, senza alcuna riflessione, senza alcuna fatica. Il meta testo drammaturgico si avviluppa intelligente sotto le braci dello spettacolo, interrogandoci sul senso della danza per noi che guardiamo e rifrangendo la domanda addosso ai danzatori stessi. Uno spettacolo che è un vero rompicapo, una sciarada, un prisma riflettente di luci e colori, in movimento costante. “Addiction”, “betrayal”, “justice” – rispondono i danzatori interpellati, fornendoci una flebile traccia, insieme alla falsa pista della comicità, che stuzzica il pubblico con la facile e autoironica presa in giro di un linguaggio, quello della danza contemporanea, che spesso rischia di essere autoreferenziale.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

Sulle rabbiose note di Ain’t got no il coro di danzatori torna indiscusso protagonista, con un affollato spiritual gestuale, che si conclude con le mani frullate in alto al cielo, come in un ecumenico hallelujah. Fino a quando irrompe nuovamente il giornalista/anchorman per proseguire la sua azione di disturbo, con un ammiccamento smaccato al pubblico: “Ok audience, the woman in the middle is Fate”. Poi, va in scena la rappresentazione dell’amor profano reso sacro dalla morte. Lei è Hanna, pallida e bionda, lui è Liam, dai tratti afro e la pelle scura. Si amano, ma il Fato li separa, condannando lui alla morte rituale. Il capro espiatorio è stato individuato. Il rito può cominciare. Il reality show sarà trasmesso in diretta. “Liam, you’ve been choosen. Wow!” –annuncia il giornalista. “You must be very excited … what are you been choosen for?” – si domanda entusiasta il cronista. “I’ve been choosen to be sacrificed” – replica Liam. “Could you describe your feelings?” –rilancia il cronista. “I have to dance myself to death” – risponde Liam. Il rituale sacrificale sembra assumere sempre più i contorni di una danza ancestrale, di soccombenti senza tempo, di ogni latitudine, che si ribellano al destino, lo catturano e lo immolano. I danzatori si stringono intorno al prescelto formando un cerchio rituale che pulsa al suono del tamburo. Il prescelto resta fermo, in ginocchio, in attesa, mentre sale un climax di voci. Il sacrificio è cominciato. Il corpo mezzo nudo del prescelto gronda di gialli post-it, che ne fanno un portatore riluttante di messaggi illeggibili e quindi indecifrabili.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

Le parole della struggente My way accompagnano l’attesa in ginocchio del prescelto, mentre i ballerini in fila schioccano a tempo le dita, a piedi nudi, in abiti color pastello, ora vagamente anni ’70-‘80. Finché una danzatrice sale sul palco e improvvisamente interrompe la cantante, mentre la TV continua a trasmettere. Il sacrificato può attendere “What is a man, what have he got / If not himself, and he had not to may the things / He truly feels not words of one for use / With that shows, I took the blows and did it my way!” – urla la ballerina mentre la cantante riprende a cantare e i ballerini schioccano le dita.

La ballata di Hollis Brown segna l’inizio della danza di morte del condannato e uno dei momenti più potenti dello spettacolo. La vittima sacrificale ruota le braccia, che improvvisamente sembrano gigantesche, enormi, infinite. Cavalca il proprio corpo con movimenti di sterno, rotea gli avambracci obbligato dal ritmo ripetitivo. La sua affannosa corsa sul posto è potentemente drammatica. La sua danza fatale si allunga in bracciate meravigliose e possenti, e nuota in archi infiniti. Poi, cade a terra stremata, sotto il giogo del destino di amore e morte al quale è stato chiamata. “Ladies and gentleman, there is a man on the floor ad his breathing is getting shallower” –commenta il giornalista.

Photo by Riccardo Panozzo

La bella Hannah piange la morte del suo Liam. Vuoto, perdita, mancanza, disperazione danzano insieme alla canzone, mentre la coppia di amanti ingaggia una toccante danza macabra, una burrascosa lotta di abbracci, di rese e di cadute, di prese e di rincorse. Il disegno acquerellato dei ballerini si giustappone al graffiante fumetto pop del presentatore e al velluto blu della colonna sonora. L’abbraccio reale della coppia di amanti sul palco – Hannah e Liam – si confonde con l’abbraccio virtuale trasmesso dalla TV. La realtà si confonde con il reality show proiettato nello schermo e i sentimenti subiscono lo stalking selvaggio esercitato dal cosiddetto dovere di cronaca, in cui la prossimità della telecamera ai corpi dei danzatori rischia di distruggere l’autenticità dell’empatia.

Che cosa sentiamo noi pubblico a fine spettacolo? “Feelings, nothing more than feelings”. Impotenza, lutto, stordimento e insieme una sordida, ribelle speranza alimentata anche dall’ambiguo coupe de theatre che chiude, a sorpresa, lo spettacolo.

Testo di Anna Trevisan

Foto di Riccardo Panozzo

Tags: #review, Ben Duke, rambert dance company