Something has changed | Dance in the Time of the Pandemic

“Before film and video, dance used to be “the evanescent art” – chorographies throughout history have disappeared while masterpieces of painting, sculpture, poetry, or theater remain for thousands of years. The widespread use of video has revolutionized the art of dance; its contribution is invaluable”.

Alkis Raftis, President of CID, the International Dance Council , UNESCO, Paris, 29 April 2020 — Dance Day.

“You think I’d crumble?

You think I’d lay down and die?

Oh no, not I, I will survive

Oh, as long as I know how to love, I know I’ll stay alive

I’ve got all my life to live

And I’ve got all my love to give and I’ll survive

I will survive, hey, hey”

Gloria Gaynor, I Will Survive

Before and After

What has been revised in the relationship between dance and video since the pandemic? This liaison dangerouse between dance and video existed has been acknowledged for some time. But it was niche, “experimental”: the so-called “vidéo-danse”, or screendance, fostered over the 1980s and 1990s (see Marie Fol, Virtualised Dance? Digital Shifts in Artistic Practices. EDN, August 2021, www.ednetwork.eu). Or, paradoxically, it was an event for the general public when (quite exceptionally) it was filmed and broadcast on television: screened dance (ibid.).

But the pandemic has not only accelerated this convergence of worlds: the physical one of the dancing body and the virtual sphere mediated by the video camera. The pandemic, despite itself, has acted as a watershed, delineating time and stage-space with a clear-cut “Before” and “After”.

First there was dance, on stage, in theatres, halls and in the physical locations dedicated to its presentation, spaces perhaps ‘regenerated’ by artful architectural reconversions. Then there was video, which from time to time flirted with dance at various festivals, thanks to a few intrepid artists or else credited to video-makers or larger camera crews who filmed performances for archival and documentation purposes or even for televised broadcast.

Post–pandemic, this relationship became evermore intense, cogent, poignant, forcing the entire world of dance to confront its double, its mirror image, encouraging it to hybridise and explore itself through new media, new situations, new ways of being, all in order to survive through the closeting and closure of theatres. The drastic and prolonged foreclosure of an otherwise well-frequented shared physical space, available to both artists and audience, has consequently redirected and propelled the entire world of dance into cyberspace.

Teatro Spazio Kor, Asti (Italy)

Hic et nunc in the digital era

And in this meteoric, conspicuous need for dance to reconfigure itself through video, so as not to fizzle out and lose its audience, the internet and social media networks have played a fundamental role, becoming de facto distribution channels which, thanks to live-streaming, has succeeded in ensuring that the public can also still attend “live” performances. Live-streaming has thus offered a welcome deliverance and a concrete response to the renowned concerns expressed by Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Benjamin wrote:

“The changed circumstances in which the product of technical reproduction may find itself may leave the consistency of the art work untouched — in any case they devalue its hic et nunc”.

In order to make up for any lack of hic et nunc (here-and-now) guaranteed by the presence of flesh-and-blood dancing bodies in the same location, during the pandemic audiences were offered the opportunity to share a “temporal hic et nunc” with the artists, made possible via livestreams of a show or a performance. With that in mind the following words by Alessandro Pontremoli, Professor of History of Dance at the University of Turin, can be fully endorsed, taken from his article Coreografie mediali dell’emergenza (Media choreographies of the emergency) translated from Atlante Magazine (21/12/2020):

“The Benjaminian opposition between technical mediation and immediacy of presence is today overcome by the awareness that dance shares with the image not so much and not only the dimension of space, but rather that of time. […] Dance is therefore alive when two bodies share imagery, time and presence. This last condition is denied on a physical level in digital mediation, but not on the level of perception and knowledge, as neuroscience has shown. […] Sharing time, memory, imagery and presence through digital technologies allows for the recovery of immediacy and the hic et nunc event through interactivity, bringing the relationship between action and perception back to the heart of aesthetic experience”.

Amina Amici in “Chiaroscuro”

Public, audience and voyeur

Without doubt something has undergone change for the general public with regard to this fruition of video-mediated performances. If interactivity and live transmission seems to have at least partially preserved that Benjaminian immediacy of the here-and-now, what about the viewer’s gaze. Today we may choose to open our inner sanctum, our home, to the world via Zoom, or perhaps you would rather remain well-hidden, switching off the camera and remaining solitary, private, just watching? In other words, what differentiates spectator from voyeur?

Once again, Alessandro Pontremoli casts light on answering this question. The following extract is from his book La danza 2.0. Paesaggi choreografici del nuovo millennio (Dance 2.0. Choreographic landscapes of the new millennium; pp. VIII-XII, Laterza, 2018):

“[…] what I wish to underscore is the centrality of the gaze in the relationship established between the person who places oneself in the situation of observing and the person who voluntarily places himself within the perspective of that gaze, in order to be looked at while one lives the experience of a dancing corporeity, an incarnation of thought about the world, capable of giving meaning to one’s dancing action”.

And he continues…

“The gaze is that of a subjectivity that recognises the other: only this process, which we can define as affective, differentiates the experience of being a true audience from the voyeuristic anomaly”.

Lavanderia a Vapore- The Dancehouse in Collegno (Italy)

The future and wreckage

Of course, many other questions remain open. For example: what place does “kinesthetic empathy” have in this kind of artistic fruition? Can the co-presence of bodies really be permanently replaced by digital synchronicity? What future might traditional festivals have? What about physical theatres? This last query is particularly pressing in Italy, given that -as Francesca De Sanctis documented in her report published for L’Espresso on 24 May 2021-

“the theatres that have reopened to the public comprise two thirds of the total number of theatres in Italy, more or less 70 percent, which corresponds to the percentage of private theatres, around 500 in all. Why? Yet the decree is clear: from 26 April 2021, within yellow zones, theatre performances open to the public are allowed to be reinstated. But under what conditions? Only a limited number of spectators and the maintenance of social distancing, factors that discourage and effectively prevent their relaunch until autumn at the earliest. Not to mention that this long period of closure has already left a great deal of wreckage in its wake”.

How long will the new rituals of this “Hygiene Theatre”, as the American journalist Derek Thompson has designated it, not only affect the enjoyment of shows and performances but also, consequently, their creation and production?

It seems difficult for both audiences and artists to give up the traditional pleasure of art and dance. The desire to carry on with the experience of live performances remains high. On the contrary, perhaps thanks to this obligatory upheaval in the production, distribution and consummation of dance, the hankering for live performances has “increased”, for audience and artists alike. At least this is what emerged from a Zoom chat with some of the protagonists of 14 Project, a special event live-streamed on 18 September 2021. A 5-hour non-stop choreographic marathon in which 19 dancers from all over the world performed their solos on empty stages, underlining their own solitude as well as the imposed segregation of us all, and showing the dispiriting emptiness of theatres that have remained abandoned. Yet, at the same time, it accentuated the acute desire to break that isolation, to continue to dance and to stay in close contact with spectators.

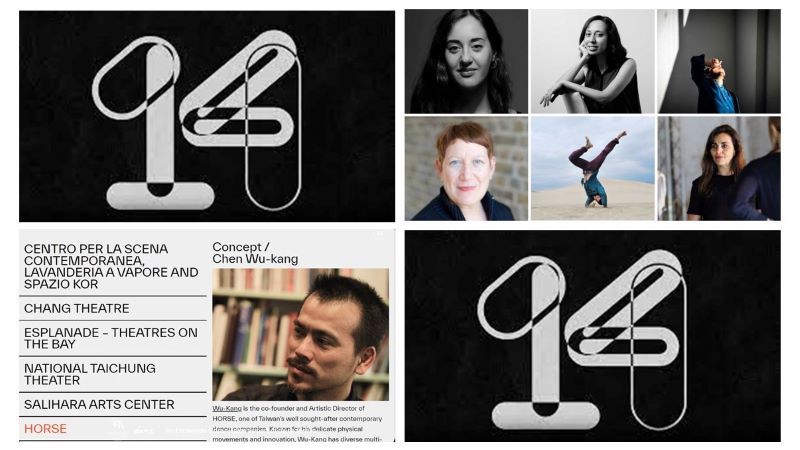

The Italian Team of the 14 Project. From top left, clockwise: Elena Sgarbossa, Greta Pieropan, Amina Amici, Susan Sentler, Manuel Martin, Marigia Maggipinto.

14 Project

Thus 14 project is a child of the pandemic. Its very title makes this explicit: 14 is the number of days of quarantine that we have all undergone or are still obliged to observe before being permitted to “return to the world”. On 18 September 2021, those 19 artists streamed themselves from Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Taiwan, Italy and ‘danced history’ in spite of themselves, embodying the state of things. But the dance of those flesh and blood bodies, alone and isolated yet globally connected through the all-seeing eye of a video camera, displayed itself in its essence: not only as a show, as a performance, as an event, but also as an irrepressible and necessary ritual form that connects mankind with himself and with the world, with beauty and with the divine.

14 project has been produced by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay together with National Theatre and Concert Hall Taipei (Taiwan) and CSC Centro per la Scena Contemporanea, Lavanderia a Vapore and Spazio Kor (Italia); Chang Theatre (Thailand), National Taichung Theater (Taiwan) and Salihara Arts Center (Indonesia).

Below is an excerpt from our Zoom interview with Wu Kang Chen, creator and head of the project, as well as with two Italian partners; dancer Amina Amici and Valentina Tibaldi of Lavanderia a Vapore.

Text by Anna Trevisan

English translation by Jim Sunderland

Video-interview by Anna Trevisan

TESTO ITALIANO

Qualcosa è cambiato | La danza ai Tempi della Pandemia

“Prima del cinema e del video, la danza era “un’arte evanescente”, nel corso della storia tante opere coreografiche sono sparite, mentre hanno resistito al passare del tempo capolavori della pittura, della scultura, della poesia e del teatro. La diffusione del video ha rivoluzionato l’arte della danza, il suo contributo è inestimabile”.

Alkis Raftis, Presidente del CID-Comitato Internazionale per la Danza UNESCO, Parigi, 29 aprile 2020, Giornata Internazionale della Danza.

“Pensavi che crollassi?

Pensavi che mi accasciassi e morissi?

Oh no, Non io

Sopravviverò

Oh fino a che saprò come amare

So che rimarrò vivƏ

Ho tutta la vita da vivere

Ho tutto il mio amore da dare

E sopravviverò

Sopravviverò (Hey-hey)”

Gloria Gaynor, I will survive

Prima e dopo

Che cosa è cambiato nella relazione tra la danza e il video dopo la Pandemia? Che questa liaison dangerouse esistesse, lo si sapeva da tempo. Ma era cosa di nicchia, per pochi, “sperimentale”: la cosiddetta “vidéo-danse”, o screendance, nata negli anni ’80 e ’90 (cfr. Marie Fol, Virtualised dance? Digital shifts in artistic practices. EDN, August 2021, www.ednetwork.eu). Oppure, paradossalmente, era evento per il grande pubblico, quello generalista, nelle occasioni in cui veniva ripresa e trasmessa (eccezionalmente) alla televisione: screened dance (cfr. ibidem).

La Pandemia però non ha solo accelerato quest’incontro di mondi: quello fisico del corpo che danza e quello virtuale mediato dalla video-camera. La Pandemia, suo malgrado, ha fatto da spartiacque, marchiando a fuoco il tempo e lo spazio scenico con un “Prima” e un “Dopo”.

Prima c’era la danza, sui palcoscenici, nei teatri, nelle sale e negli spazi fisici dedicati, magari spazi “rigenerati” da sapienti interventi di riconversione architettonica, e poi c’era il video, che di tanto in tanto flirtava con lei nei festival di danza grazie ad alcuni spericolati artisti o grazie alle riprese e alle registrazioni di cameramen ed operatori realizzate a scopo di archivio e documentazione o per essere trasmessi in TV.

Dopo la pandemia questa relazione è diventata più intensa, cogente, struggente, costringendo l’intero mondo della danza a confrontarsi con il suo doppio, a guardarsi allo specchio, a ibridarsi e ad esplorarsi attraverso nuovi media, nuovi luoghi, nuovi modi di esistere, per poter sopravvivere all’isolamento e alla chiusura dei teatri. Così la drastica e prolungata preclusione di uno spazio fisico comune e condiviso a disposizione degli artisti e del loro pubblico ha dirottato l’intero mondo della danza nel cyberspazio.

Teatro Spazio Kor, Asti

“Hic et nunc” ai tempi del digitale

E in questo veloce e drammatico doversi riconfigurare della danza attraverso il video per non soccombere e non perdere il proprio pubblico, hanno giocato un ruolo fondamentale Internet e i social network, diventando di fatto un canale di distribuzione che, grazie al live-streaming, è riuscito a garantire al pubblico di poter assistere anche a spettacoli “dal vivo”. Il live-streaming ha offerto così ideale sollievo e concreta risposta alle celebri preoccupazioni espresse da Walter Benjamin in L’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua riproducibilità tecnica. Scriveva infatti Benjamin:

“Le circostanze in mezzo alle quali il prodotto della riproduzione tecnica può venirsi a trovare possono lasciare intatta la consistenza intrinseca dell’opera d’arte – ma in ogni modo determinano la svalutazione del suo hìc et nunc”.

Per sopperire alla mancanza del hic et nunc garantito dalla presenza di corpi danzanti in carne ed ossa nello stesso luogo, al pubblico ai tempi della pandemia è stata offerta l’opportunità di condividere con gli artisti un “hic et nunc temporale”, reso possibile dalla trasmissione in diretta e online di uno spettacolo o di una performance. Risultano quindi pienamente condivisibili le parole che il prof. Alessandro Pontremoli, docente di Storia della danza all’Università degli Studi di Torino, ha scritto in Coreografie mediali dell’emergenza (in Atlante Magazine, 21/12/2020):

“L’opposizione benjaminiana fra mediazione tecnica e immediatezza della presenza è oggi superata dalla consapevolezza che la danza condivide con l’immagine non tanto e non solo la dimensione dello spazio, quanto piuttosto quella del tempo. […] La danza è viva dunque quando due corpi condividono immagini, tempo e presenza. Quest’ultima condizione se è negata sul piano fisico nella mediazione digitale, non lo è però sul piano della percezione e della conoscenza, come le neuroscienze hanno messo in luce. […] Condividere tempo, memoria, immagine e presenza attraverso le tecnologie digitali permette il recupero dell’immediatezza e dell’evento hic et nunc attraverso l’interattività, riportando al centro dell’esperienza estetica la relazione fra azione e percezione”.

Amina Amici in “Chiaroscuro”. Foto d’archivio

Pubblico, audience e voyeur

Qualcosa è indubbiamente cambiato anche per il pubblico nella fruizione di spettacoli mediati dal video. Se l’interattività e la diretta sembrano aver perlomeno parzialmente preservato quell’immediatezza benjaminiana dell’hic et nunc, che cosa ne è stato però dello sguardo dello spettatore, che spesso ha potuto scegliere se aprire al mondo la porta di casa propria via Zoom o se invece rimanerci ben nascosto, oscurando la videocamera per rimanere solo a guardare? Altrimenti detto: che cosa fa la differenza tra spettatore e voyeur?

Ancora una volta le parole di Alessandro Pontremoli illuminano i tentativi di risposta a questa questione. Scrive infatti Pontremoli nel suo libro La danza 2.0. Paesaggi coreografici del nuovo millennio (pagg. VIII-XII, Laterza, 2018):

“[…] quello che mi preme sottolineare è la centralità dello sguardo nella relazione che si stabilisce fra chi si pone nella situazione di osservare e chi si colloca volontariamente entro la prospettiva di quello sguardo, per essere guardato mentre vive l’esperienza di una corporeità danzante, incarnazione di pensiero sul mondo, in grado di dare senso al suo agire danzante”.

E prosegue:

“Lo sguardo è quello di una soggettività riconoscente dell’altro che lo riconosce: solo questo processo, che possiamo definire affettivo, differenzia l’esperienza dell’essere vero pubblico dall’anomalia voyeuristica”.

Lavanderia a Vapore – Casa della danza, Collegno (Torino)

Il futuro e le macerie

Certo, restano comunque molte altre questioni aperte. Ad esempio: che spazio ha l’ “empatia cinestetica” in questo tipo di fruizione artistica? Davvero la compresenza dei corpi è surrogabile in modo permanente dalla sincronicità digitale? Che futuro hanno i festival tradizionali? E i teatri fisici? Domanda, quest’ultima, particolarmente urgente nel nostro Paese, visto che – come ben ha documentato Francesca De Sanctis nel suo report pubblicato per L’Espresso del 24 maggio 2021–

“[…] i teatri che hanno riaperto al pubblico sono i due terzi del numero totale di teatri in Italia, più o meno il 70 per cento, che corrisponde alla percentuale di sale private, circa 500 in tutto. Perché? Eppure il decreto parla chiaro: dal 26 aprile 2021, in zona gialla, tornano gli spettacoli aperti al pubblico nelle sale teatrali. Ma a quali condizioni? Numero limitato di spettatori e distanziamento, fattori che scoraggiano e impediscono la ripartenza, almeno all’autunno. Senza contare che questo lungo periodo di chiusura ha lasciato dietro di sé già tante macerie”.

I nuovi riti dello “Hygiene theater”, come lo ha battezzato il giornalista statunitense Derek Thompson, quanto a lungo incideranno nella fruizione degli spettacoli e delle performance ma anche, di conseguenza, sulla loro creazione e produzione?

Sembra difficile sia per il pubblico che per gli artisti rinunciare ad una fruizione tradizionale dell’arte e della danza. Il desiderio di poter continuare a fare esperienza anche di spettacoli in presenza resta grande. Anzi, forse proprio grazie a questo stravolgimento obbligato della produzione, della diffusione e della fruizione della danza è stato il desiderio di danza dal vivo ad esserne uscito “aumentato”, non solo tra il pubblico ma anche tra gli artisti.

Perlomeno è quanto emerge dalla nostra chiacchierata con alcuni dei protagonisti di 14 project, uno speciale evento trasmesso in live-streaming via Zoom. Una maratona coreutica di 5 ore no stop in cui 19 danzatori da tutto il mondo hanno interpretato i loro assoli su palchi vuoti, sottolineando la propria solitudine e quella di tutti noi e mostrando lo sconfortante svuotamento dei teatri rimasti deserti di pubblico eppure sottolineando il fortissimo desiderio di rompere quell’isolamento, di continuare a danzare e di restare in contatto con il pubblico.

Il gruppo di lavoro italiano di 14 project. Da sinistra in senso orario: Elena Sgarbossa, Greta Pieropan, Amina Amici, Susan Sentler, Manuel Martin, Marigia Maggipinto.

14 project

14 project è dunque un progetto figlio della pandemia. Lo si evince già dal titolo: 14 è infatti il numero dei giorni di quarantena che tutti noi siamo stati o siamo ancora obbligati a rispettare prima di poter “ritornare al mondo”. In quel 18 settembre 2021 quei 19 artisti in collegamento streaming dall’Indonesia, dalla Thailandia, da Singapore, da Taiwan e dall’Italia hanno danzato loro malgrado la Storia, incarnando lo stato delle cose. Ma la danza di quei corpi in carne ed ossa, soli ed isolati ma globalmente connessi grazie all’occhio di una videocamera, si è mostrata nella sua essenza: non solo come spettacolo, come performance, come evento, ma anche come insopprimibile e necessaria forma rituale che (ri)connette l’uomo con se stesso e con il mondo, con la bellezza e con il divino.

14 project è una produzione Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay ed è stata coprodotta da National Theatre and Concert Hall Taipei (Taiwan) con CSC Centro per la Scena Contemporanea, Lavanderia a Vapore e Spazio Kor (Italia); Chang Theatre (Thailand), National Taichung Theater (Taiwan) e Salihara Arts Center (Indonesia).

Qui di seguito un estratto della nostra video intervista via Zoom con Wu Kang Chen, ideatore e responsabile del progetto, e con alcuni dei partner italiani coinvolti: la danzatrice Amina Amici e Valentina Tibaldi di Lavanderia a Vapore.

Testo di Anna Trevisan

Video-intervista a cura di Anna Trevisan

Tags: #digitaldance, Boarding Pass Plus